The viewer scans the composition for clues about what has just happened and what might come next. If you want to show action, consider which part of the narrative has the most suspense, what Howard Pyle called the “Supreme Moment.”

To an extent, a painting can avoid showing action and can downplay the passage of time. Most of Vermeer’s paintings seem to exist in a kind of eternal present. Edward Hopper’s paintings (Nighthawks, above) often depict people waiting in an enigmatic suspense.

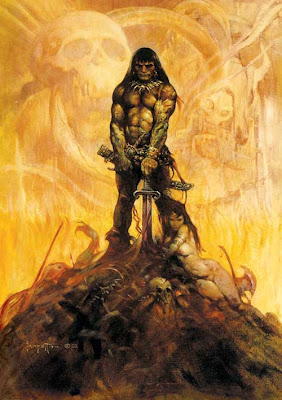

In this book jacket by Frank Frazetta, the Conan character is standing ready for action, leaving the threat for the reader to imagine. The design is stable, with the figure rising above the clutter of corpses below, his sword held in vertical stillness.

In this book jacket by Frank Frazetta, the Conan character is standing ready for action, leaving the threat for the reader to imagine. The design is stable, with the figure rising above the clutter of corpses below, his sword held in vertical stillness.Pyle advised his students that “to put figures in violent action is theatrical and not dramatic.” He said that “in deep emotion there is a certain dignity and restraint of action which is more expressive.” The terror before the murder or the remorse afterward is more interesting than the act itself.

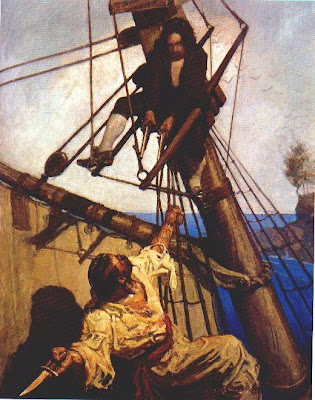

Most dramatic sequences build suspense toward a climax. Here in a pivotal moment of Treasure Island, Jim Hawkins and Israel Hands face each other in a life-or-death exchange. The outcome of the next moment is uncertain.

Most dramatic sequences build suspense toward a climax. Here in a pivotal moment of Treasure Island, Jim Hawkins and Israel Hands face each other in a life-or-death exchange. The outcome of the next moment is uncertain. Often the Supreme Moment happens during a fateful meeting or departure. It could be the meeting of hero and villain, prisoner and captor, or lover and betrothed. Above, Ilya Repin shows the heartwrenching departure of a young recruit leaving the family farm.

Often the Supreme Moment happens during a fateful meeting or departure. It could be the meeting of hero and villain, prisoner and captor, or lover and betrothed. Above, Ilya Repin shows the heartwrenching departure of a young recruit leaving the family farm. N. C. Wyeth often chose a still moment that spoke for a larger story. Here a young worker pauses while sipping the cool water that the girl has brought him.

N. C. Wyeth often chose a still moment that spoke for a larger story. Here a young worker pauses while sipping the cool water that the girl has brought him. Tomorrow we'll look at the appeal of peak action.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét