As blog reader R8R mentioned this in yesterday’s comments, Eadweard Muybridge began systematically photographing running horses as early as 1877.

As blog reader R8R mentioned this in yesterday’s comments, Eadweard Muybridge began systematically photographing running horses as early as 1877. This began as a way to settle a bet about whether a horse really had all four feet off the ground at a single time. The photos proved that it does, but not quite in the way artists had imagined. At the moment when all four feet are off the ground, they’re gathered under the horse’s belly, not kicked out front and back.

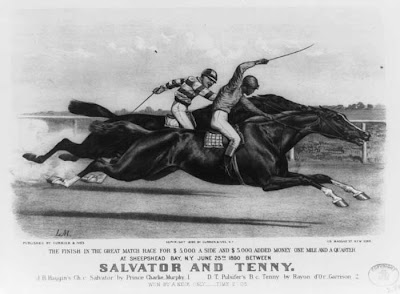

This began as a way to settle a bet about whether a horse really had all four feet off the ground at a single time. The photos proved that it does, but not quite in the way artists had imagined. At the moment when all four feet are off the ground, they’re gathered under the horse’s belly, not kicked out front and back.According to the photographic evidence, the Currier and Ives picture was inaccurate, even though it was done after Muybridge’s photos were available.

Muybridge’s evidence must have been hard for artists to digest at first. Modern painters like Marcel Duchamp, to their credit, were grappling with how to capture the dynamics of action in a single painting. There’s no easy or right way to do it, despite my promise at the end of yesterday’s post.

Muybridge’s evidence must have been hard for artists to digest at first. Modern painters like Marcel Duchamp, to their credit, were grappling with how to capture the dynamics of action in a single painting. There’s no easy or right way to do it, despite my promise at the end of yesterday’s post. Yesterday we looked at three paintings of people walking. All of these paintings were based on poses that a model could hold in a static position. Although Wyeth and Rockwell certainly had access to fast-action photos of people in motion I suspect that candid action photographs didn’t “look right” to them.

Yesterday we looked at three paintings of people walking. All of these paintings were based on poses that a model could hold in a static position. Although Wyeth and Rockwell certainly had access to fast-action photos of people in motion I suspect that candid action photographs didn’t “look right” to them.A lot of you commented in praise of yesterday’s paintings, and I agree. Cormon’s image has gravitas; Rockwell’s has a stateliness, and Wyeth’s a desperate urgency. But I think they’re successful despite their posing of action. Not only are the poses all the same in each picture, they're not consistent with the realism of the rest of the treatment, and I think a painting that shows an action has to be convincing not only as a singular, static image, but also as a moment in a larger conception of movement and time.

Since Muybridge, the notion of what “looks right” has changed somewhat. Most of us wouldn’t accept the standard Currier and Ives pose for running horses anymore. We accept photographic action effects, like the blurring of a moving foot, for example.

Most illustrations by the mid twentieth century that show action poses—like this advertising illustration by Austin Briggs—tended to rely on candid action photography for paintings of action scenes. As a work of art, this one is a bit silly, but clearly he did his homework and really posed models in the action.

Most illustrations by the mid twentieth century that show action poses—like this advertising illustration by Austin Briggs—tended to rely on candid action photography for paintings of action scenes. As a work of art, this one is a bit silly, but clearly he did his homework and really posed models in the action. Tom Lovell also clearly studied action photography for this painting of Alexander for National Geographic. To my eye, this painting is successful in terms of movement because it conveys both the timeless epic and the snapshot incident.

Tom Lovell also clearly studied action photography for this painting of Alexander for National Geographic. To my eye, this painting is successful in terms of movement because it conveys both the timeless epic and the snapshot incident.Thanks to Leif Peng for the Austin Briggs image, link.

Muybridge on Wikipedia: Main article, and assorted animated gifs.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét